The elusive quest for sustainable off-grid electrification: new evidence from Indonesia

September 2023

Mike Duthie (Social Impact), Jörg Ankel-Peters (RWI – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research), Carly Mphasa (Social Impact), and Rashmi Bhat (Social Impact)

Portfolio evaluation of US Millennium Challenge Corporation’s Green Prosperity Program in Indonesia – new evidence indicates that older concerns about the sustainability of mini-grids and off-grid energy systems have not gone away

Providing reliable and powerful electricity to the hundreds of millions who are still lacking access remains a major global challenge. Mini-grids, fed by renewable energy sources like solar, hydro or biomass, can play a central role for remote last-mile areas or sparsely populated countries, supplying the powerful electricity of the centralized grid at lower cost than grid expansion. Over the past decade or so, costs of mini-grids and other off-grid renewable energy (RE) equipment (scaled by unit of installed capacity) have decreased tremendously, primarily due to cost declines for panels and batteries. However, sustainable operation of mini-grids and RE technologies remains elusive. Since typical off-grid RE programs only subsidize the initial investment, operators must generate sufficient revenues to cover Operational and Maintenance (O&M) costs.This, in practice, has proven to be very difficult.

The idea behind most off-grid RE electrification programs is a market-based paradigm: long-term financial incentives for operators are supposed to create a basis for sustainability. These long-term financial incentives, though, are contingent on being able to charge a cost-covering tariff and, oftentimes, on revenue growth from increasing demand (e.g., from new customers, or growth of economic activities using RE). A recent evaluation conducted by Social Impact of a program implemented with these objectives, provides new evidence on the question of long term RE sustainability. The evaluation’s findings suggest that many technologies in the portfolio have not been able to successfully manage sustainability challenges, four years post-commissioning.

Overview of the 24 Community-Based Off-Grid Grants

Image: Project Sites Across Indonesia

From 2013-2018, the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), in partnership with the Government of Indonesia (GOI), invested $56.4 million in a portfolio of 24 community-based off-grid (CBOG) RE grants that aimed to increase productivity and reduce reliance on fossil fuels by expanding access to reliable renewable electricity. Grantees proposed the RE technologies taking account of the local economic context and available renewable energy resources. The technology utilized ranged from stand-alone systems of solar and hydro-power water pumps (3 grants), biogas digesters (2), solar home systems (3), and solar plants targeted at single entity productive use (5), as well as mini-grids in solar (5), hydro (8), and biogas (1 grant; some grants utilized multiple technologies). The scale of RE investments varied substantially across the portfolio, ranging from a disbursement of $38,264 for construction of a solar water pump in one village, to $9.8 million for the construction of three solar mini-grids and one water pump across three villages.

Evaluation Finds that Most Projects Performed Below Expectations

We conducted an extensive ex-post performance evaluation following a Baseline (2018) and Interim impact evaluation (2020) of the CBOG portfolio, including in-depth case studies of six grants. For 23 grants, we collected data through document review and protocols, and also surveyed grantees and beneficiaries (one grant consisting of a single biogas digester was excluded from the evaluation). For the in-depth case studies, we conducted interviews with local government, grantees, and beneficiaries at the RE sites.

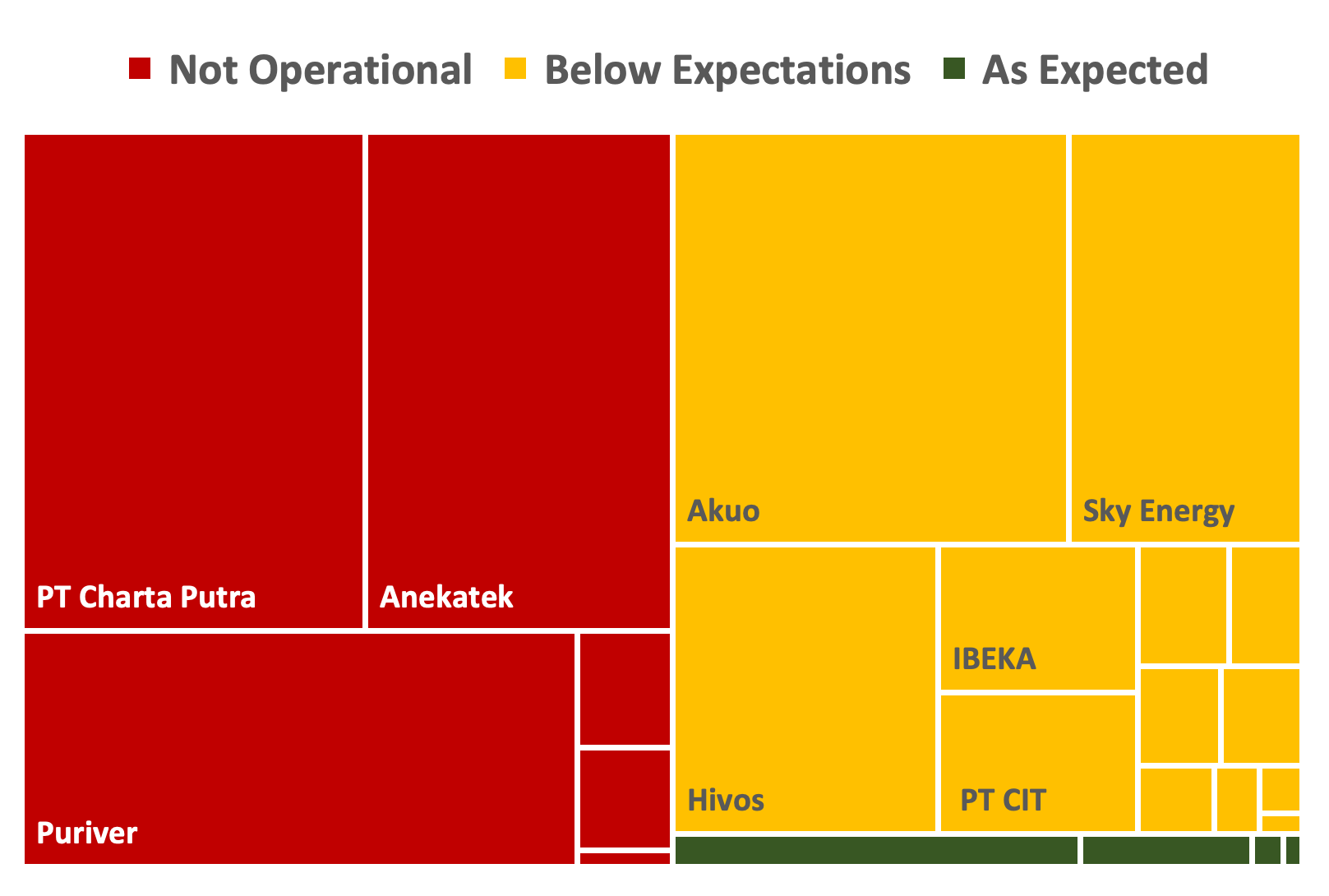

Overall, we find poor functionality of grant-funded infrastructure across the portfolio, with many technologies defunct or no longer in use. A quarter of the grant-supported projects were completely non-operational at endline – these six projects accounted for roughly 50 percent of the overall investment ($28.7 million). Another 13 grants were operating well below expectations, representing an additional 47 percent of the portfolio’s RE investment ($26.5 million). Only four grants were functioning in line with expectations across their entire grantee portfolio. These four grants were simpler in their scope (operated in a single location each and provided only one type of RE technology), and at $1.3 million represented a mere two percent of the portfolio’s RE investment.

Figure 1: Functionality status four years post commissioning. Size of boxes reflect the magnitudes of RE disbursement in USD (Names of smaller grants have been omitted due to limited space).

Main Issues: Market-Based Paradigm, Lack of Resources, Overstated Projections

Importantly, the implementation context of the CBOG-RE grants is similar to that of other decentralized RE projects. Specifically, such projects are typically located in remote areas far from the centralized grid and, as a consequence, are also far away from other key infrastructures (such as quality roads and vibrant market exchanges). Access to agricultural products is difficult in such areas, and non-agricultural incomes are largely absent. Therefore, many decentralized RE projects, for example those in this investment portfolio, serve a target population with a low ability to pay. The CBOG RE projects did attempt to stimulate economic activity by establishing agriculture production houses, providing equipment for processing and packing of products, as well as training community members on processing agricultural products. Our evaluation revealed, though, that only a third of production houses were active at endline due to faulty machinery, limited working capital and community motivation, and low market access. In sum, these decentralized RE projects primarily served a target population with a low ability to pay. Complementary measures to stimulate productive energy use, essential to the project’s sustainability approach, were not successful.

This leads to a situation in which high operation costs meet insufficiently low revenues. On the costs side, the transaction costs of running an off-grid model in the remote regions where decentralized RE projects tend to be implemented are very high. Reasons include: underdeveloped financial services; a lack of technically trained staff; lack of spare parts; high transportation costs. In our endline grantee survey, only seven grantees (32 percent) believed that the target communities had adequate knowledge and access to technical support to carry out major repairs. Only three of these seven (14 percent overall) believed that these communities also had the necessary financial resources to carry out major repairs. Moreover, quality control mechanisms were not adequately integrated into the projects. The most common reason why technologies were non-operational was that needed major repairs had not been undertaken. A need for any major repairs so soon after implementation severely threatens sustainability, as financial and management systems have not been well established at that stage, and cash flows are shaky. In the evaluated portfolio, nine grants reported major equipment failure due to severe weather events that are common in Indonesia, such as lighting strikes, cyclones, and flooding. Outside of weather events, at least four grants had major equipment quality deficiencies, particularly those with solar-charged batteries. Under these conditions, revenues from tariffs are not high enough to cover O&M costs.

In terms of revenues, an important challenge was that obtaining sufficient financing for O&M was a big issue for most of the portfolio grants. Even for mini-grids that utilized pre-paid meters, low consumption levels by connected users constrained revenue potential. Most mini-grids overestimated demand in the planning phase, anticipating higher commercial and residential take-up. While 86 percent of grantees in the endline survey noted that demand for the technology was as anticipated, beneficiary and on-the-ground verification revealed multiple instances where demand failed to meet the projections made in grantees’ business models. This leads to a dilemma: under a market-based paradigm, the mutual occurrence of high costs and low demand would require very high tariffs to sustain operations. High tariffs, though, are at odds with the low ability to pay in remote rural communities, and with government regulations that often do not allow tariffs to exceed those paid by consumers connected to the national grid.

Counterclockwise from top left: (1) Community serviced by mini-grid, (2) Household with both SHS and grid connection, (3)Exterior of Micro-Hydro Power Turbine House, (4)Refrigeration previously powered by defunct mini-grid.

Conclusion

The findings from this evaluation are aligned with much of the recent impact evaluation literature on rural electrification, for example for on-grid extension into previously unserved rural areas in Kenya, Rwanda, and Tanzania. The take-away for future off-grid and mini-grid programs is that project designs and accompanying business models should be scrutinized more critically, especially with regards to assumptions about demand and prospects for economic growth, given other features (presence and access to markets and complementary infrastructure) of the connected areas. Simply adding elements geared at stimulating productive use does not address the underlying market-connectivity challenges, and may therefore even further increase risks. In most rural areas, this will reveal a tension between required demand trajectories and tariffs.

A potential approach for funding agencies is to work on sustainable subsidy schemes that not only support the initial investment, but also ensure sustainable operation of mini-grids. This could be in the spirit of results-based financing (RBF) approaches, but with ‘results’ that are based on sustained connections, or could operate via a kWh-based subsidy akin to a feed-in tariff. Both design options are not easy to implement and require careful examination in the planning phase and ongoing monitoring during the implementation phase. These measures will make mini-grid projects more expensive in the first place, but the goal would be to achieve greater long-term success and cost-efficiency, as demand grows over time.

See MCC’s Evidence Platform for our evaluation report and more information on the program and the evaluation including a lessons learned memorandum.