Climate finance myth busting

Climate finance to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) to help mitigate and adapt to climate change will be at the center of debate next week in Egypt at the 27th annual UN climate conference. Issues on the table range from investment targets for developed countries, loss and damage, programs and reforms of key institutions, and more. What follows are five important and commonly misunderstood concepts that I frequently encounter in this space, along with my best attempt at unpacking them.

Myth #1: Corporate NetZero and ESG commitments are driving private sector investment to low-carbon projects across the Global South.

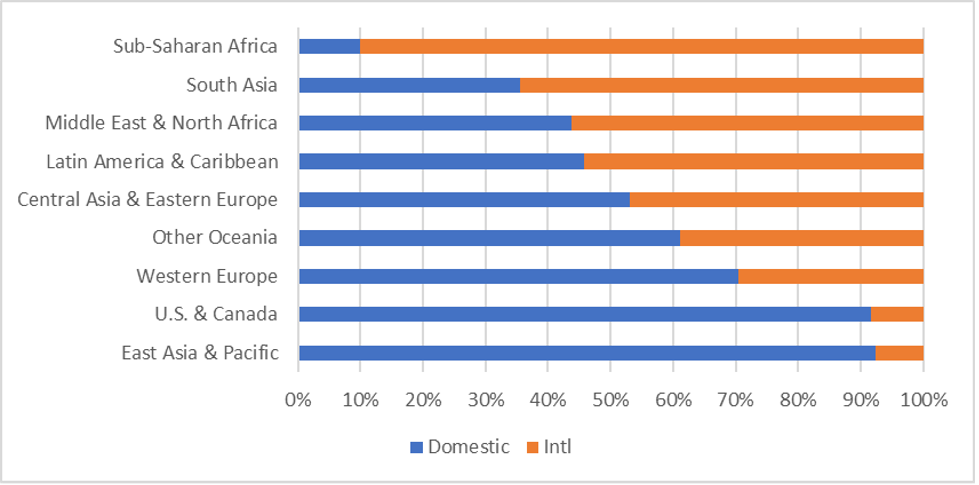

There’s been a blur of announcements from the private sector over the last year regarding climate equity, inclusivity, and sustainable development. But the fact is, the private sector is largely checked-out of many lower-income markets. Across all of sub-Saharan Africa, only 10% of climate investment is sourced privately. In South Asia, about one-third. As seen in Figure 1, this compares to 95% of climate investment in the US and Canada coming from private sources.

Figure 1: Destination region of climate finance, by public/private (USD billion, 2019/20 annual average)

Source: CPI, Global Landscape of Climate Finance 2021

This is important because of shifts in who owns capital over the past 70 years. Private capital under management has grown from $250 billion in the 1950s to more than $111 trillion today and is expected to reach $145 trillion by 2025. The holdings of institutional investors like pension funds, insurance companies, and endowments are now 900 times larger than the balance sheets of the World Bank and all the multi-lateral development banks (MDBs) combined.

Public coffers alone are simply insufficient to fund the low-carbon transition, especially in developing countries where pandemic-related borrowing has left governments buried in debt.

To be sure, there are excellent reasons that private investors are avoiding many of these markets. They generally have higher political and regulatory risks, currency risk, and other risks exogenous to the project or firm so carry with them a higher capital cost right out of the gate. Something like 88% of the developing world holds sub-investment grade credit ratings or no ratings at all, putting entire countries outside the reach of many institutional investors.

Private sector actors need to educate themselves on emerging markets, bring perceived risks into line with real risks, and put their ESG money where their mouth is. Doing so would not only make their ESG and NetZero rhetoric more genuine, but entering these emerging markets is good business in the long-term. Populations and economies are growing and urbanizing so rapidly in parts of Africa, for example, that by the end of the century, 13 of the largest 20 cities in the world are likely to be in Africa, including the three largest. But as we’re seeing with apparent dissention within the ranks of the big banks party to the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (a collation of 450 financial institutions that pledged to bring their $130 trillion in collective assets to net zero by 2050): private investors will not be forced into sectors or geographies.

The private sector will need help and handholding from the MDBs and development finance institutions (DFIs) that know these markets well and can offer tools to lower the risk of private investment. MDBs and DFIs have changed relatively little over the past several decades to adapt to the shift in capital ownership. Now is the time to re-orient goalposts around de-risking, private capital mobilization, and transformation. Check out the report we did on this last month for a more detailed discussion on reform pathways.

Myth #2: The Green Climate Fund and related “multi-lateral climate funds” are the primary mechanisms for delivering climate investment to low- and middle-income countries.

I hear this almost every day in one form or another, and it’s painfully wrong. If we don’t understand where climate investment is coming from, we can’t talk about effectively reforming public finance institutions, supporting countries in building financeable project pipelines, or scaling investment.

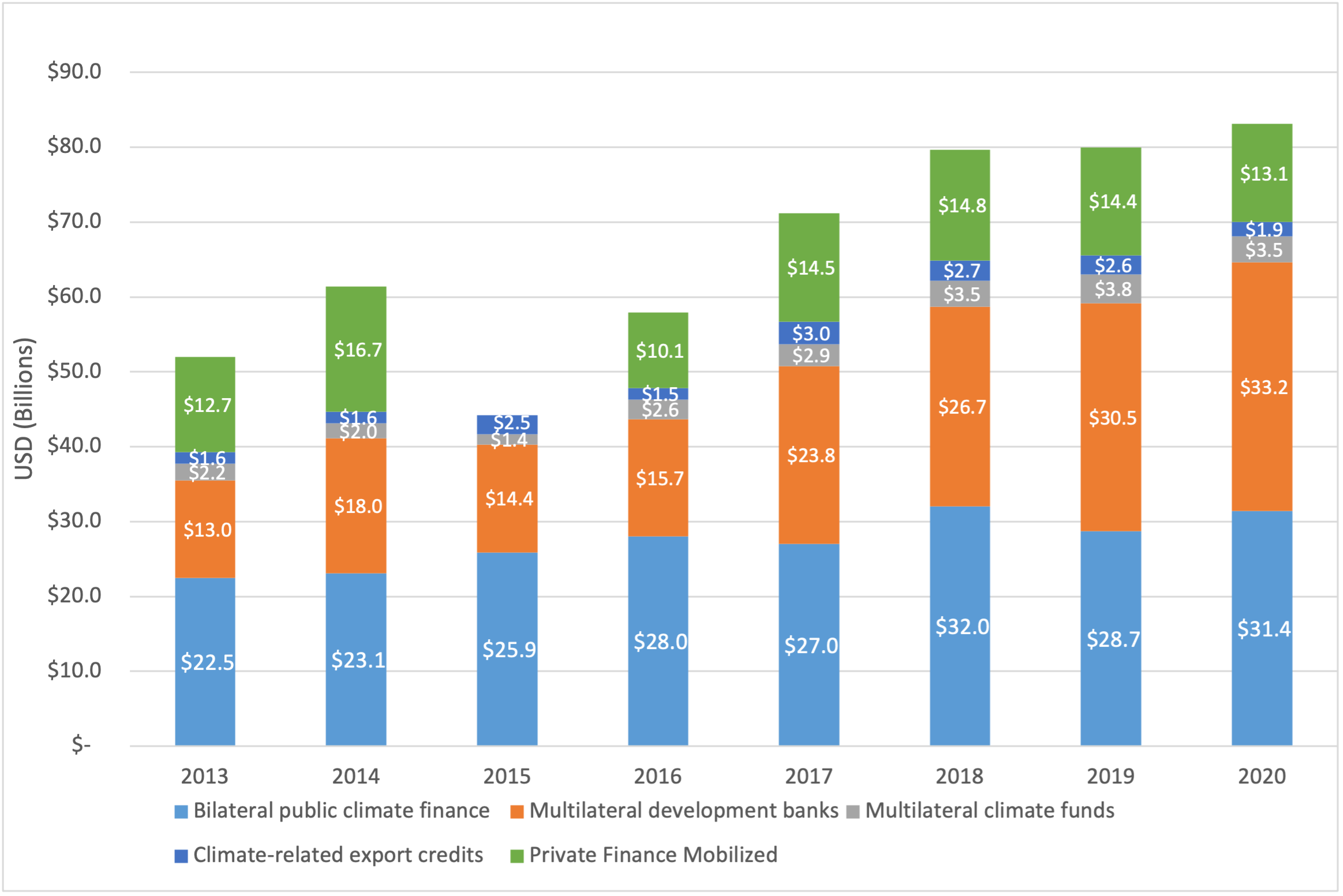

As seen in Figure 2, the multilateral climate funds (MCFs) represented $3.5 billion in investment in 2020, or just 4% of the $83 billion in climate investment mobilized from to developing countries.

Figure 2. Climate finance provided and mobilized by developed countries, 2013-2020

The Paris Agreement sets out a framework for an equitable partnership between high-income countries and LMIC destinations of climate finance, which is to be allocated according to the needs of LMICs as set out in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). HOWEVER, only the institutions explicitly tied to NDC implementation under the Paris Agreement—the Green Climate Fund, the Global Environment Facility, the Adaptation Fund, etc. (collectively, the “multilateral climate funds”)—have any obligation whatsoever to program investment around those NDCs.

Instead, developed countries are opting to direct the vast majority of their financing through their DFIs and the MDBs. These are institutions with deeper and longer experience working with LMIC governments, and where advanced country governments can exert greater control as shareholders and board members. They are also more nimble than multilateral climate funds in many cases. As a result, climate investments to LMICs have not so much been determined by NDC needs as by a host of other factors, including geopolitical relationships, mitigation opportunities, commercial interest, and even export opportunities from advanced countries.

Of enormous importance here is that the principle financial tool of MDBs and DFIs is market-rate debt. This form of capital may be a poor fit for climate projects that produce public goods and are unable to generate sufficient financial returns to repay market debt (ie most adaptation projects). These projects are generally dependent on a much smaller pool of grants and concessional debt (typically in the form of low- or zero-interest loans), tools that are relatively more prevalent with the MCFs. Grant financing accounts for only about 6% of overall climate investment globally. This dynamic puts low-income countries (LICs) at a distinct disadvantage in attracting financing, as projects in these markets tend to have higher levels of overall risk and lower expected returns.

Myth #3: If advanced countries would just follow-through on their $100 billion investment commitment, new low-carbon development pathways would materialize in LMICs.

At the Copenhagen Conference of Parties (COP) in 2009, parties agreed that developed countries would mobilize $100 billion annually to developing countries beginning in 2020 to help mitigate and adapt to climate change. Aggregate investments mobilized in 2020 were about $83 billion, falling short of the target.

To be sure, developed countries must deliver on that $100 billion commitment to begin building trust. However, the financing challenge runs far deeper than whether advanced country governments muster $80 billion or $100 billion or even $200 billion annually—the latter figure representing the hypothetical future fulfillment of the call included in the Glasgow Climate Pact for developed countries to double their investment commitments to developing countries (a doubling was “urged” but not required).

None of these figures correlate with the level of investment needed. It is estimated that LMICs will need an additional $800 billion annually by 2025, and close to $2 trillion a year by 2030, to meet climate mitigation and adaptation goals. The International Energy Agency estimates $1 trillion is needed annually in developing economies for the energy sector alone, a level that would require a seven-fold increase in investment.

Increasing LMIC climate investment “from billions to trillions” needs to be about more than arbitrary investment targets. It will require the mass mobilization of private capital; the alignment of NDCs with the realities of climate investment instruments and institutions; and connecting technical assistance, development finance, aid, export credit, and philanthropic resources in new ways that demonstrate and scale low-carbon technologies and business models faster. It will require overcoming incumbent North-South technology transfer biases embedded in MDB and DFI financing approaches that lead to a failure to support Global South–led innovation and applications. And it will require a focus on building green financial systems across the developing world that can deliver investment through pandemics, wars, and climate disasters without getting distracted. Relying on fickle foreign capital—as most developing regions disproportionately do (see Figure 3)—is an insecure and unsustainable investment strategy if ever there was one.

Addressing each of these issues will require extensive coordination and political will. None of them will be achieved just because the $100 billion target, or other arbitrary targets, are met.

Figure 3. Share of domestic and international climate finance flows by region of destination (2019/2020 annual average)

Source: based on CPI data from Global Landscape of Climate Finance, 2021

Myth #4: NDCs are a driver of low-carbon investment.

Being party to the Paris Agreement means a country has to come up with a “Nationally Determined Contribution” to global efforts to fight climate change. Thus far, these NDCs have largely failed to drive enabling environment reforms and financing pathways needed to support low-carbon development.

In some LMICs, the first round of NDCs—which are to be updated every five years—was a useful process that drove domestic engagement of various stakeholder groups and helped to identify and quantify national climate priorities. In others, a few hired consultants got together with a few local ministry officials and some words were put on paper. Either way, the process tended to leave behind capital providers and key actors that could contribute to a better alignment of the policies with viable investment approaches.

NDCs and climate plans are too frequently limited to an emissions target and inventory of possible actions and projects. These tend to neither translate into a roadmap of policies and investments, nor add up to deliver the long-term targets implied in the NDC. The end result is a consistent inability to connect NDCs to financing.

A rigorous, inclusive process that defines a low-carbon development vision nationally and locally can not only help to mobilize capital to aligned project pipelines. It can raise levels of ambition and ensure the legitimacy of climate regimes. The process on display in South Africa being driven by the Just Energy Transition Partnership—as well as groundwork being laid in India, Indonesia, and other countries for similar undertakings—may provide important lessons on how engagement processes can help drive sustainable pipelines of private sector investment.

The next iteration of NDCs should reflect local priorities—like jobs—and engage key constituencies that can support delivery of bankable projects. NDC debates should be mainstreamed into development policy debates and vice versa. The process should include consultations with capital providers, the private sector (especially SMEs), climate-relevant line ministries (energy, agriculture, transport, water, etc.), subnational governments, civil society, and underrepresented groups (especially women, youth, and indigenous peoples). Early engagement with these actors—in combination with a transparent and accountable decision-making process—can facilitate bottom-up mobilization of local knowledge and sectoral expertise, translate high-level objectives into specific investments, and better identify viable financing options to enable implementation. Initiatives that channel private and public investors to projects that not only advance climate outcomes but also elevate community voices and address socioeconomic inequities can build public backing and accelerate project development.

Myth #5: Adaptation investment in LMICs is increasing rapidly.

I’m going out on a limb on this one. Some data says I’m wrong. According to developed country reporting, adaptation investments in LMICs grew 69% between 2018 and 2020, from $16.9 billion to $28.6 billion.

I suspect that a significant part of what is going on here is DFIs and MDBs—the source of the bump in adaptation figures—are getting better at analyzing and labeling many adaptation-related activities, especially as their leadership has increased the pressure to deliver adaptation investment.

In contrast to mitigation investments, it can be difficult to identify and measure investments in adaptation and resilience. These types of projects can take a range of forms and are far from a well-defined set of activities. Adaptation projects frequently cut across sectors. They sometimes take the form of specific measures like early warning systems or coastal erosion protections. Or they could be schools, roads, bridges, and other traditional infrastructure that must be made more resilient to climate change. There is an institutional learning curve to properly identifying, quantifying, and tagging adaptation investments, and we’re moving up that curve right now.

Keep in mind, it has taken many years for developed countries to align on what they count as “climate finance,” even on the more straightforward mitigation side. Until relatively recently, for example, Japan was including investments in coal plants in Indonesia and Uzbekistan as climate finance in filings to the OECD because, they argued, the investments supported more efficient technology than options these countries were poised to otherwise employ. Institutions can get far more creative than that when it comes to tagging adaptation and resilience projects. And reasonable people can take different approaches to calculating the incremental “adaptation component” of a project.

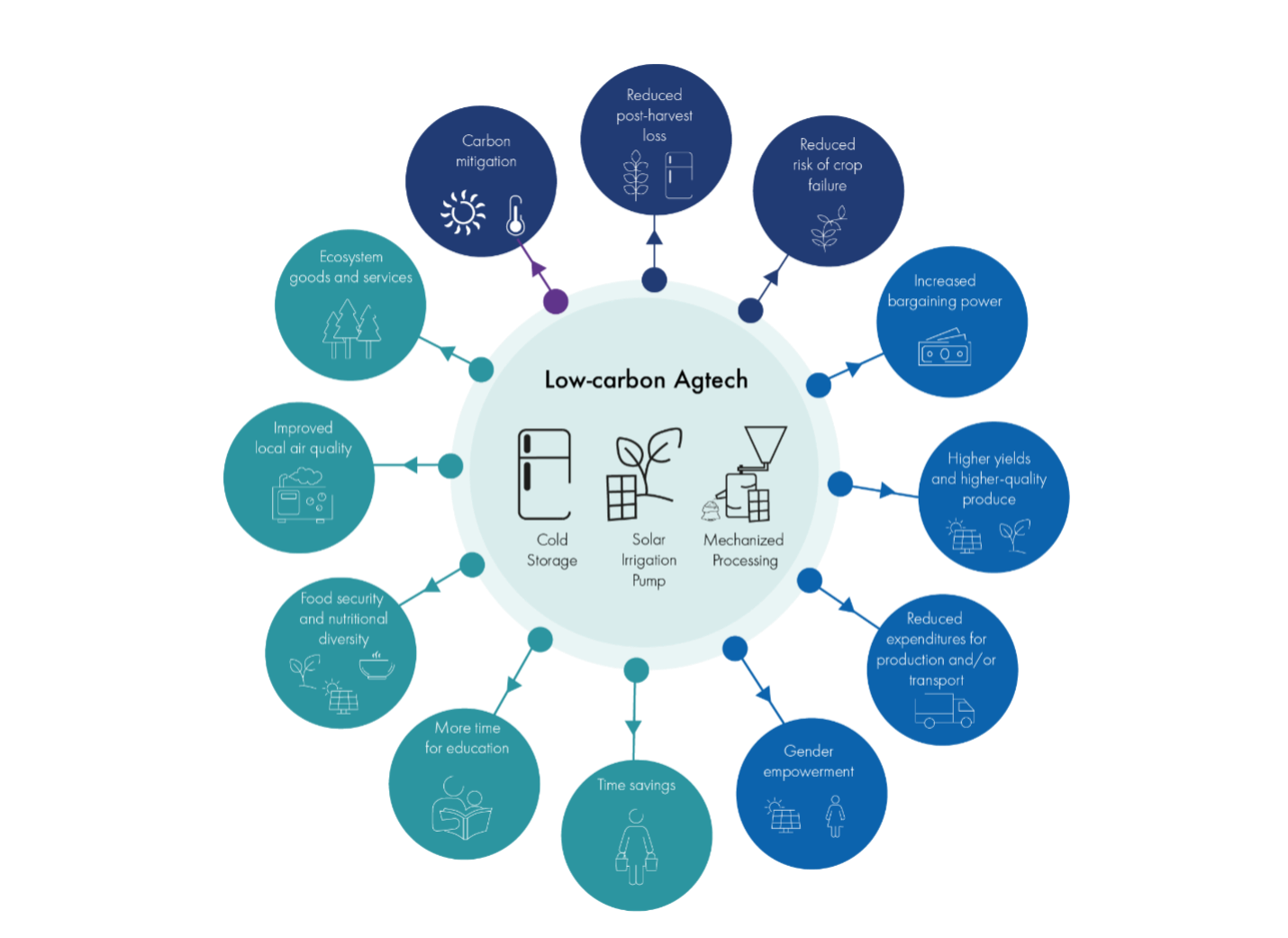

Figure 4 illustrates some of the adaptation-related benefits that can accompany investments in certain climate smart agriculture technologies. Can you imagine the dilemma faced in the back offices of MDBs when they’re deciding whether a project that increases farmer bargaining power or leads to greater female empowerment or reduces post-harvest loss should count as adaptation investment and how much of it should be counted?

Figure 4: Contributions of low-carbon agriculture technologies to climate adaptation and mitigation

Note: Dark blue circles represent direct adaptation benefits; light blue circles represent direct enhancement of adaptive capacity. Green circles indicate indirect enhancement of adaptive capacity, and the purple circle represents mitigation benefits.

Source: Catalyzing Climate Finance for Low-Carbon Agriculture Enterprises, 2022

One flag to look for in the reporting data as a signal that adaptation investment is actually increasing—as opposed to being more accurately (or creatively) tagged—is a shift in investment instruments. Many adaptation projects do not generate sufficient financial revenues to repay market-rate debt so must have significant shares of concessional funding in their capital structure. The 69% increase in reported adaptation investment is not accompanied by notable changes in the deployment of concessional capital at the MDBs and DFIs.

Onward!

Climate investment can be a useful lens from which to view the pace, scale, and challenges of low carbon transformation and development. But the numbers, terminology, and conflicting agendas spilling out of different stakeholders within the ecosystem can make it a confusing and fraught lens as well. What common misunderstandings do you confront in this space? Where could additional clarity be helpful? Let us know! Energyaccess@duke.edu

Want to be notified when we publish new blog posts?