COVID-19 has exposed the carbon cost of innovation

The coronavirus pandemic caused the greatest global recession since the Second World War, and the largest ever annual decline in carbon emissions. Never has the link between economic activity and our use of fossil fuels been so starkly exposed. How did human civilization become so dependent on releasing carbon into the air?

The answer lies in the history of innovation. Innovation is rarely about inventing an entirely new product or service. More often, it’s about making things cheaper. And making an existing product or service cheaper means that more people can benefit from that product or service, whether it’s cars, hamburgers, or air conditioners. However, almost everything that’s become so cheap and affordable today, is cheap and affordable because we’ve worked out how to maximize the use of a one-time source of energy—fossil fuels. Cheap, widely consumed, and fossil-fuel dependent products and services are why the world’s economy is so tightly linked to emissions of carbon. Nowhere is this better represented than with the journey from the Library of Alexandria to the smartphone in your pocket.

When you pick up your smartphone to ask it a question, you’re not enjoying a privilege that’s new to the twenty-first century. You—and the other 4.5 billion people who used the internet last year—are just enjoying a privilege that was once only available to the Pharaohs of Egypt. The Pharaohs could also ask almost any conceivable question, and have it answered—not through the internet, but through the Library of Alexandria.

The Royal Library of Alexandria

The Library of Alexandria was first conceived around 300 BC by Demetrius of Phalerum, an advisor to Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter of Egypt. Demetrius convinced Ptolemy to establish a “universal library” that contained a copy of every book in the world. At its peak, the Library housed 500,000 papyrus scrolls and employed 100 scholars. The Pharaoh could ask questions on everything from drama and literature, to mathematics, anatomy, geography, physics, and astronomy—and have it answered.

The drive to create a truly universal library became a hallmark of the Ptolemaic dynasty. Ptolemy III’s hunger for knowledge was so great that he decreed that all ships docking at the city’s harbors should surrender their manuscripts to the authorities. Never had so much knowledge been housed under one roof.

With the cavernous Library of Alexandria, the Ptolemaic dynasty achieved the first iteration of what tech companies would build two millennia later: the smartphone that fits in your pocket. They organized the world’s information and made it accessible by finding a way to do three essential things—store information; search and retrieve information; and finally, something we now take for granted—the ability to read after the sun goes down. What Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and others achieved with digital files, search engine algorithms, and LEDs, Ptolemy and Demetrius achieved with papyrus scrolls, an army of scholars, and sesame oil lamps. The biggest difference lies in the cost. Each of these three technologies—storage, retrieval, and light—are now between one hundred thousand and one trillion times cheaper than they were in Ptolemy’s time.

How two millennia of innovation made accessing information one trillion times cheaper

Let’s start with light. Over the last 2,000 years lighting technology has moved on from oil lamps to candles, to incandescent lightbulbs, to compact fluorescent lamps, and most recently to LEDs. Professor William Nordhaus, winner of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economics, famously charted the historic decline in the price of light in terms of the buying power of a worker’s wage. He estimated that an hour’s work today will buy about 350,000 times as much illumination as could be bought with an hours’ work by a common laborer using a sesame oil lamp to light the Library of Alexandria.

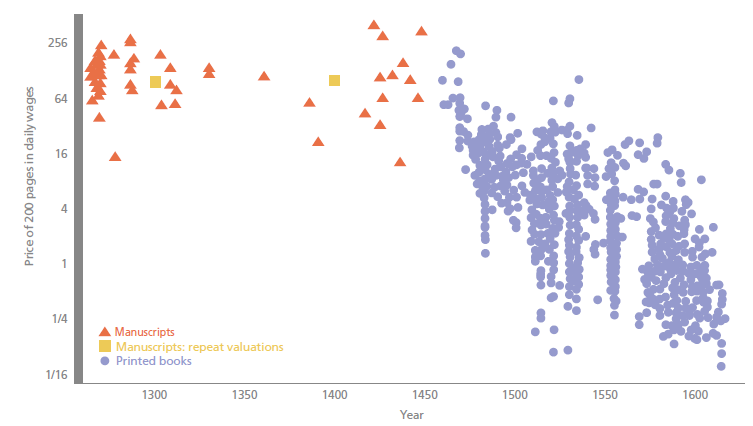

The equivalent breakthrough moment for storing information was the Gutenberg printing press. Research by the economist Jeremiah Dittmar and the data scientist Skipper Seabold shows that in the early 1200s, a manuscript of 200 pages cost the same as 200 days’ wages for an unskilled laborer. Following the introduction of printing, prices declined rapidly, falling to one day’s wages by 1600. The next step change in cost was the digitization of information. A worker on the United States’ federal minimum wage can now afford the price of storing a 200-page book every 5 seconds—making information storage 3.2 million times more affordable today than 2,000 years ago.

The prices of manuscripts and printed books from Dittmar and Seabold’s research. Source: LSE Impact of Social Sciences blog, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported.

But even this enormous fall in price is dwarfed by what has replaced Ptolemy’s army of scholars—Google’s search engine algorithm PageRank. PageRank, and the other algorithms Google has since developed, sorts through hundreds of billions of web pages to find the most relevant results in a fraction of a second. Computer algorithms as a technology aren’t new; it’s just that previously they were prohibitively expensive. Ada Lovelace is credited with writing the first computer program in 1843 for the polymath Charles Babbage’s Analytic Engine. However, despite the British Government investing £17,000 in Babbage’s endeavors, twice the cost of a warship at the time, he was never able to complete it. A steam engine-based computer was simply too expensive.

Ada Lovelace and a copy of her manuscript containing a formula that is often recognized as the first computer program. Source: Moore Allen & Innocent.

The turning point for retrieving information was the invention of the transistor in 1947, 76 years after Babbage’s death. This brought the cost of one calculation per second down to around $1,000 dollars in 1960. By the year 2000, a single dollar bought 10,000 calculations per second. Today a dollar buys one billion calculations per second. Costs have declined by a factor of one trillion.

Computing has followed Moore’s Law for more than a century. Source: Ray Kurzweil via Wikimedia Commons.

These cost declines are hard to comprehend. We live in a world of price cuts of 50% off, maybe 75% on Black Friday. But what does it mean for something to be 100,000 cheaper (99.999% off), or a trillion times cheaper (99.9999999999% off)?

It means that today, 4.5 billion people are Egyptian Pharaohs in sharing their ability to ask almost any conceivable question, and have it answered. That’s the number of people that have access to the world’s current universal library—the internet.

We find these exponential falls in cost in almost every part of human life—agriculture, energy, transport, communication. Agricultural yields, for instance, now deliver ten times more food energy from each acre on average than in the early 1900s.

And yet these massive declines in cost don’t tell the whole story.

The inconvenient truth about innovation

The phenomenal reductions in economic costs have been driven as much by fossil-fuel based forms of energy as by human ingenuity. Consider agriculture, where a 10x increase in yields has been driven by a 90x increase in energy inputs, largely in the form of fossil fuels for farm machinery, irrigation pumps, and fertilizers. Even the less resource-intensive information and communication industry that’s behind the smartphone in your pocket currently accounts for 3% of the world’s carbon footprint. This is forecast to rise to 14% by 2040 as the energy needs of data servers increase, and smartphones require more energy to manufacture and mine their raw materials.

This is the carbon cost of innovation. Almost everything that’s become so cheap and affordable today is cheap and affordable because we’ve worked out how to maximize the use of a one-time source of energy—fossil fuels. It’s the fundamental tension between human progress and the pressure it puts on our planet. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns we have just 10 years to avoid the most severe consequences of global warming. This is what former United States Vice President Al Gore called “An Inconvenient Truth.”

Technological innovation can help us reduce the economic cost of things so that everyone lives long and healthy lives. But our greatest challenge is to decouple the economic growth that supports higher livings standards from increased carbon emissions. The coronavirus pandemic has shown how great a challenge this will be.

Making energy miracles happen

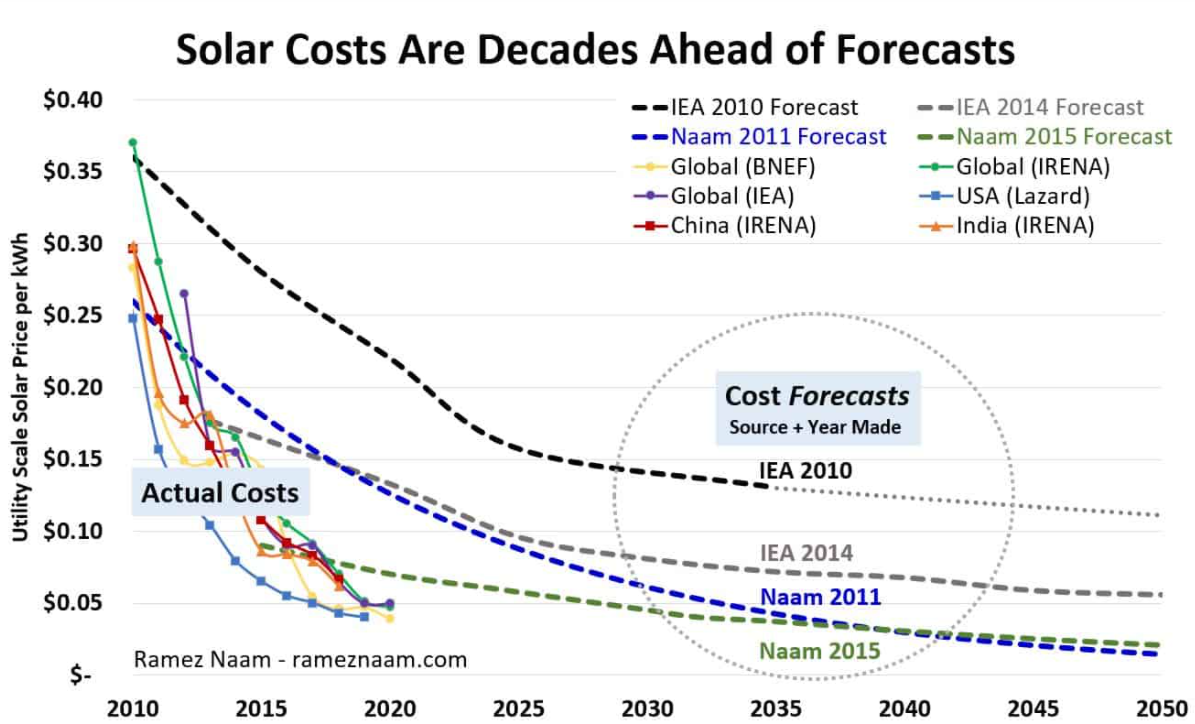

Pharaoh Ptolemy I could hardly have imagined how many of his subjects’ descendants would enjoy the same privileges—and more—that he did. And humanity’s ability to innovate has repeatedly confounded even the most experienced forecasters. The cost of solar PV is 30 to 40 years ahead of what experts forecast in 2010.

The cost of solar PV has dropped faster and lower than almost anyone has expected. Source: Ramez Naam.

We need this same energy miracle to happen in every part of the economy, not just electrification: transport, heating, plastics, fertilizers, cement, etc. However, at current levels of R&D funding, we’re unlikely to achieve this. For example, the U.S. government currently spends $30 billion a year on health research, compared to just $6 billion a year on energy research.

The Library of Alexandria was a miracle of its time. It became a hallmark of the Ptolemy dynasty after their relentless focus and continuous investment in building the world’s first universal library. A relentless focus on carbon-free technologies must become the hallmark of this generation’s governments.

Comments? Questions? Suggestions for future posts?